At just before 6pm on Wednesday evening, Thomas and I crossed the finish line of our ride across Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. I’d chosen Ascension Cathedral as the end point – a famous Almaty landmark and somewhere that was likely to give us a sense of occasion. It didn’t disappoint, and waves of emotion washed over me as we cycled the final few metres to the steps below its main door. Huge pride in what we had achieved. Overwhelming satisfaction that I’d reached this place almost entirely under my own pedal power from home.

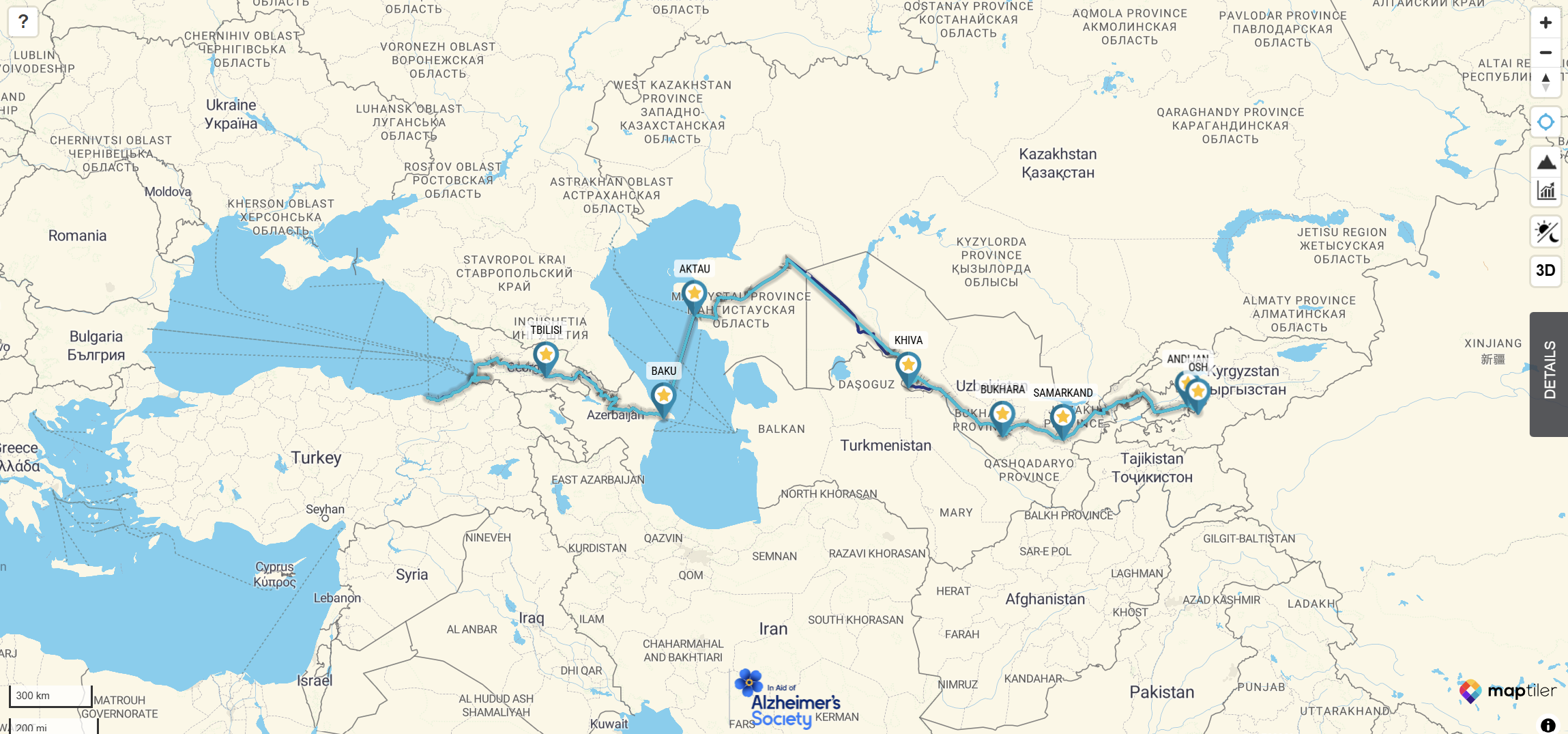

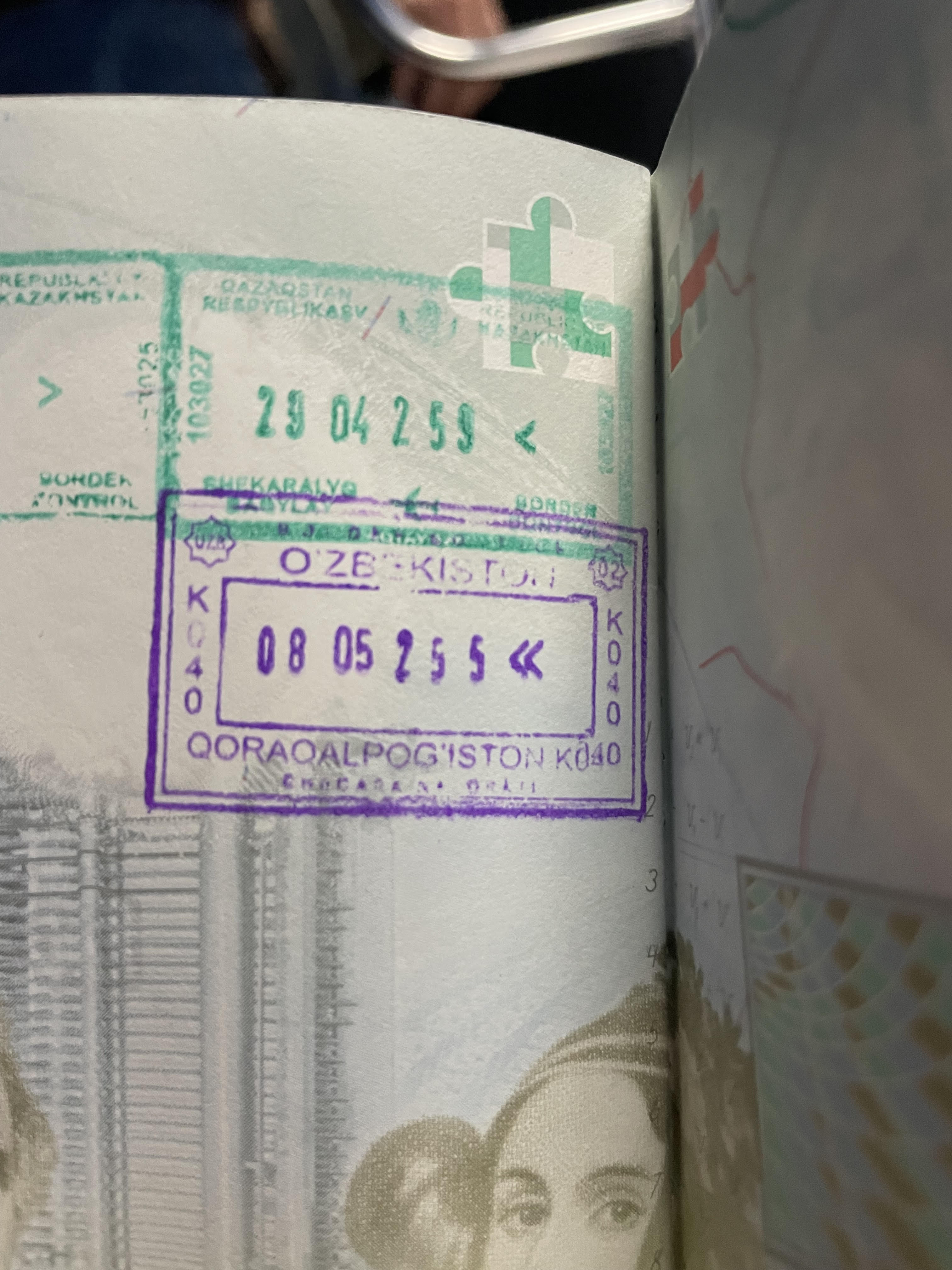

I’ve tried to ride every kilometre I could from home to here in order to create as near a continuous route as possible. The connections between the place I live and the world I discover from converting wanderlust into progress around the globe matter to me. There have been some enforced exceptions on a journey that’s now almost a third of the way around the world in its fruition; I had to cross the English Channel and the Caspian Sea by boat and by plane respectively, I had to catch a train across the Kazakh/Uzbek border because of its closure to all road traffic, and last week’s landslide in Kyrgyzstan led to our taking a car ride to avoid a 600-kilometre diversion. But apart from those interruptions, I’ve made the journey from Sussex to Almaty entirely by bicycle.

It’s been a journey of 83 days, 6,091 miles, 9,866 kilometres, across 14 countries, with 77,267 metres (253,500 feet) of vertical elevation.

Our ride of 246 kilometres through this eastern part of Kazakhstan from Kegen to Almaty (split across two days) felt at times like a mirror of the ride I did through the west of this vast country, whose land mass is equivalent in size to the whole of western Europe, in May. The remoteness, the absence of shops and civilisation, and the need to wild camp and focus on the basics of survival (in particular sourcing water) had loud echoes of my adventure through the western Kazakh desert some 26 cycling days previously. With the remoteness and the rawness of the experience comes something mystical and deeply rewarding – an adventure sharpened by the imperative to focus on the few simple but vital things required to shape our journey (and keep us functioning!).

The distance we had to cover across our last two days was eminently feasible (and consistent with our daily kilometrage on the other days of this ride), but the temperature built on the day north from Kegen to 37c, a headwind that announced itself that day only grew in intensity and irritance the following morning, and the road surface was highly changeable and in places very difficult to traverse. Cyclists talk about ‘grippy’ roads, and grippiness makes such a difference to the power output required to cover a given distance. At times, a broken or bumpy road surface can feel like a quagmire drawing one in to its inner reaches. Combined with the invisible foe of a strong headwind, the riding conditions over the final two days of our ride were often draining.

For the penultimate night of our ride, we would have accepted a camping solution a lot less appealing than the one that presented itself to us within a short distance of the start of the swathe of land that we’d earmarked for finding a spot. It was magical – alongside a fast-flowing chalky river in which we washed ourselves (just about avoiding cold-water shock!) and our kit. We pitched our tents on relatively flat ground, and tried to see off a large army of midges with liberal application of Jungle Formula. We cooked on our Trangia – some delicious and very spicy ramen noodles, and then pasta with tuna and cheese. With culinary expectations realistically low, it turned out to be a very satisfying supper!

Lying in my tent beneath the stars following an early sunset (given Kazakhstan’s adoption of a universal time zone which brings an early start and an early end to the day in the eastern areas of the country), I reflected on our adventure (and on the wider arc of my ride from home to here across 83 days on my bike). An adventure like this yields incredible moments – some planned, some serendipitous, and so many of them are the basis for memories that not just last a lifetime, but shape a lifetime.

Those moments are so often synonymous with the people who colour them. There are the remarkable people whose own adventures provide untold inspiration and kinship – a vibrant community of cyclists who criss-cross the planet carrying their hopes, dreams and idiosyncrasies. Borne of different life stories. But all united in a love of this world, a desire to achieve something tangible, and on the whole finding great pleasure in celebrating the rich tapestry of people they encounter as they make their way around the planet. It was fun to meet Steve from Wales as he took a break on the Koldomo Pass, and to hear him tell us that he’s riding “from Wales to Wales”! We met Kate Leeming, an Australian extreme endurance cyclist and explorer, in Kyrgyzstan on her epic ride along the course of the Naryn River in aid of water.org; and we crossed paths with cyclists from Czechia, Switzerland, France, Ecuador and Japan as they turned the pedals in pursuit of their own unique goals.

And then there are the people whose lives couldn’t be much more different from our own, but our interactions with whom have been as life-enhancing as any. The man who gave me a thumbs up and a smile as we headed in to Bokonbayevo at the end of a long and arduous day in the saddle will never know what a shot in the arm it was to feel his warmth and encouragement. There have been one or two exceptions to the almost universal affection we’ve been shown – including, disappointingly, a couple of truck drivers who seemed indignant at our presence on their roads in eastern Kazakhstan and appeared to try to drive us off the road, with horns that on almost every other occasion throughout Central Asia have been blasted supportively being used in a much more hostile way. But they have been huge exceptions. Time and again, we’ve been shown great kindness and respect, with so many gracious strangers wanting to know what they could do to help us.

And one person has shaped this adventure more than any other. Riding with Thomas has been unbridled joy. Being a father and son out on the road together, united in our determination to do something special, has been one of the great privileges of my life. I’ll never forget it, and I’ll never take for granted the opportunity to have experienced the very best of life.