I looked up at the moon from the Silk Road city of Bukhara a fortnight ago and marvelled at its orientation in the sky. The most familiar quadrant (including the Sea of Tranquillity, where Apollo 11’s Eagle module touched down in 1969) had rotated in the sky and occupied a position between about 2pm and 3pm on a clockface instead of between 4pm and 5pm, as it does in the UK. With the clouds set to clear tomorrow in Kyrgyzstan, I’m looking forward to seeing the full extent of the swivel since leaving home!

I remember visiting an observatory in Australia when I travelled there in 1992 and being struck by the fact that from the southern hemisphere the moon was upside down (compared to the face it wore when seen from the UK). But I’d travelled to Australia under the power of trains and planes (roughly 50% of the journey in each). In Bukhara, it was almost entirely my own pedal power that had afforded me this new perspective, and as a marker of my progress it was a perspective that moved me.

Hand in hand with the motivation to see how far I can travel on my bike goes a constant fascination with these markers of progress. The moon’s presentation in the sky is a striking celestial measure, but there are some fun terrestrial ones too. Crossing over into Kyrgyzstan yesterday added another hour on to the time, which means I’m now a more distant five hours ahead of UK time; and as the crow flies I’m only about 70 miles from the Chinese border.

Osh, the second biggest city in Kyrgyzstan and just an eight-kilometre ride from the Uzbekistan border, provided my finish line yesterday, and with a large dump of snow having fallen overnight at altitudes lower than those I’d have had to scale to ride much further, my decision to end this leg here has been vindicated.

Kyrgyzstan became the 14th country of my ride from home (including the UK), and it’s taken me a cumulative 75 days to get here. The thrill I feel in crossing a country border by road shows no sign of diminishing as I head east around the globe. I love the sense of anticipation that builds in the final kilometres before a border post as freight trucks queue to pass through customs and immigration, and I relish the crescendo of activity that accompanies the passage of humans and traffic from one country to another.

This particular crossing, which I made with Bijou, the British cyclist I’ve overlapped with since arriving in Beyneu (Kazakhstan) and whom I’ve ridden with a bit over the last few days especially, was relatively smooth, with relief that the paperwork on the Uzbekistan side (which can apparently be a bit onerous) was painless, and some surprise that the Kyrgyzstan half of the process was so speedy.

I know that it’ll take some time to digest everything I’ve experienced on this ride from Turkey to Kyrgyzstan, and there’s so much to reflect upon that I think rushing that process would do the adventure a disservice. But there is some immediate frame of reference from having reached the end of this ride.

I spent 32 days on the bike, and another 19 days off it – mostly sorting the complex logistics that allowed the 32 days to happen!

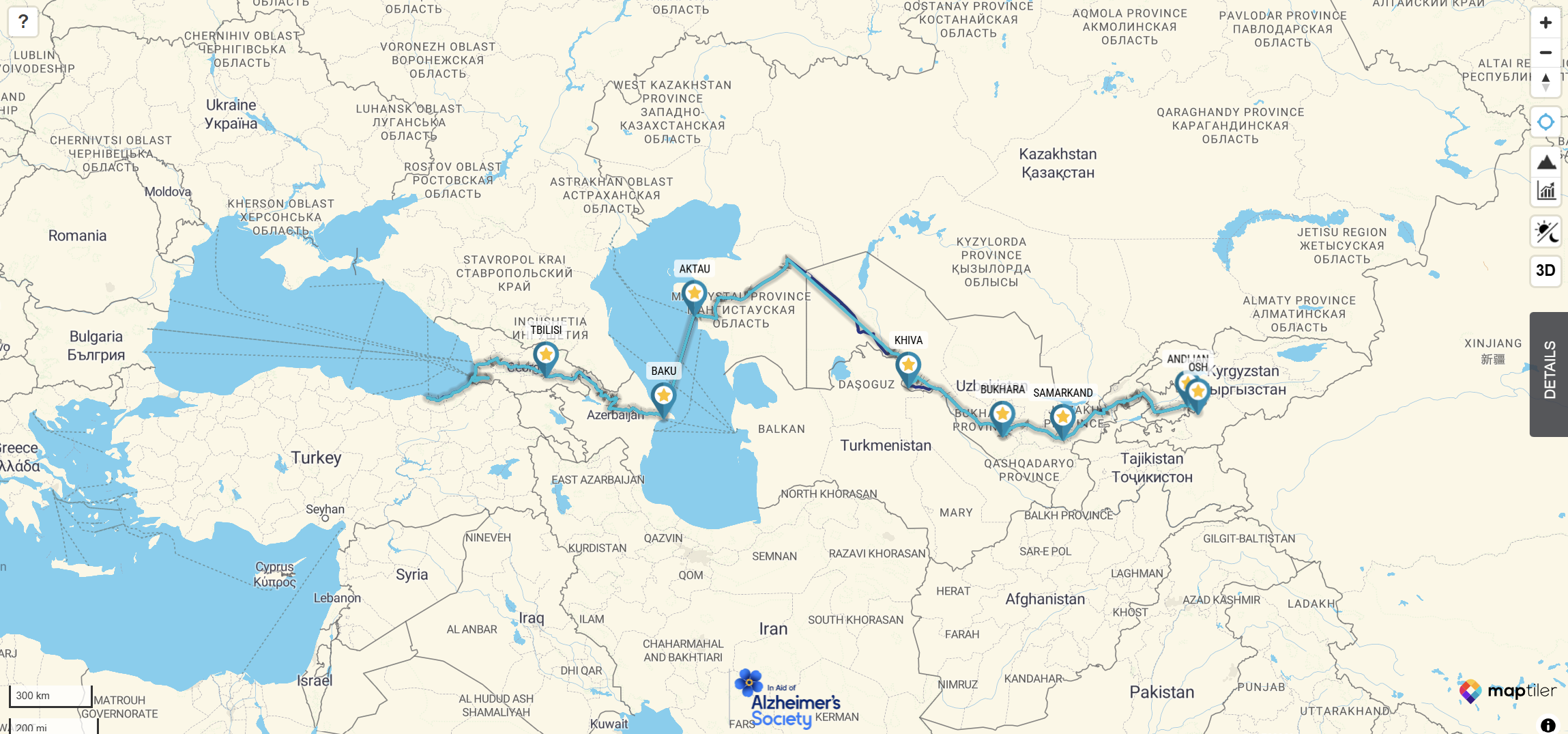

I crossed the eastern part of Turkey in bitterly cold and wet conditions, encountered an extreme blast of winter in western Georgia, and then enjoyed embracing spring as I rode from the Black Sea to the Caspian Sea across Georgia and Azerbaijan.

On the east side of the Caspian, I stared out across the abyss of the desert from Aktau and felt intimidated by the journey that lay ahead; but I made it through the vast wilderness of that part of western Kazakhstan (wild camping in the remoteness of the desert as I went), and I headed on down to Uzbekistan, with the help of a train to cross the border, which was closed to road traffic when I reached the area (and will now, it’s just been announced, remain so until at least 1 September).

Uzbekistan brought some incredibly challenging cycling, with enormous tracts of desert being baked in unseasonable 43-degree heat. As so often on a bike, however, I found great reward for the hardship – in the shape of the remarkable Silk Road cities of Khiva, Bukhara and Samarkand. And, later, the mountainous ride from Angren to Kokand was a hugely aesthetic antidote to the harsh industrial surroundings of the Almalyk and Angren areas.

There have been plenty of challenges to face since I set off from Trabzon in Turkey. Thankfully, there was only one further puncture over 31 days and 3,260 kilometres after those that beset me on day one in Turkey after just 12 and 30 kilometres respectively! There were other consternations to cope with though: intense loneliness, stomach issues in Georgia, the closure of a key pass in the Georgian mountains that meant a three-day rerouting of my ride, having to haul my bike through 30 kilometres of wet clay where a road was being rebuilt in Georgia, being told I couldn’t board the sleeper train from Baku back up to the border town of Balakan in Azerbaijan, battling the howling headwind of the Mangystau region of Kazakhstan, developing an infection that required Kazakh antibiotics, a crash that wrecked the mountings on one of my panniers, and having to replace my rear tyre (yes tyre; not inner tube) three (yes, three) times owing to damage from troublesome road surfaces.

But there are a plethora of things to feel grateful for too, and those things far outweigh the adversities. I had no major illnesses or injuries. And throughout the journey across six countries I often felt sucked along by the affections of people who wanted nothing in return for their kindness. I experienced acts of pure generosity (countless gifts of food, water, and help in many forms), but most of all the relentless positivity of people who provided encouragement along the way.

There was an orchestra of friendly truck, van and car horns across the 32 days on the bike, with truck drivers far and away the most animated of road users. Perhaps there’s a natural affinity and respect between two species of long-distance traveller? And there was constant engagement along the road through interactions that usually began with a “where are you from?” and were almost always backed up with fist pumps, hands to the heart and other gestures of genuine warmth. So many times those gestures provided solace when the going got tough.

We live in a world that’s increasingly fractured and vulnerable to political actors who seek to exploit people’s fears and aggravate their prejudices. My antipathy towards those actors was strong before I set off on this adventure, and it’s hardened during it. There is so much inherent goodness and shared humanity in people, and so much benefit to be had in celebrating and fostering those truths.